January 2024: The Iliad reading guide

Welcome to the Ancient World Book Club!

The Ancient World Book Club is a monthly book club where we alternate between reading ancient texts and books by modern authors who were inspired by the ancient world: historical fiction, myth retellings, and everything in between!

It’s a democratic process, and every month I take suggestions and run a poll to see what our next read will be (February 2024 will be Natalie Haynes’s Stone Blind!). Each book club is held on Storygraph, where I invite members to a reading group where we can discuss the text.

The Iliad is the first ancient text we voted for - an ambitious choice! - and I hope that this guide and the resources I’ve pulled together will help us all to understand and enjoy the first six books of this hugely influential text.

You can join the discussion in our Storygraph reading group by clicking here.

Introduction to the Iliad

What is the Iliad?

The Iliad is around 15,000 lines of epic poetry, thought to have been completed in roughly the form that we can now read it around 750BC. It tells a story of the semi-mythical Trojan War, and is centred around a few weeks of action towards the end of the 10 year battle.

What is epic poetry?

Epic poetry is narrative poetry: it’s poetry that tells a story. It’s written in hexameters, a flexible poetic metre that’s based on the length of syllables.

Homeric epic is written in Homeric Greek, an artificial poetic language made up of a mixture of Ancient Greek dialects from different regions and different time periods. It’s a flexible language that helps the poet to fit his words to the metre of the verse and although it isn’t a language that is spoken in everyday life, it’s easy and straightforward to understand. Or at least, it would have been for the intended audience!

Listen to how the beginning of Book 3 of the Iliad sounds being read aloud in its original language:

Here are some stylistic features of epic poetry that you might want to look out for as you read the Iliad:

Epithets: these adjectival phrases describe the essential characteristics of a character, place, or object, such as swift-footed Achilles or Agamemnon, lord of men. The poet uses epithets to help him to fit the meter as he composes, which means that they can sometimes be found when a character isn’t behaving in the way they’re described - Achilles can still be swift-footed, even when he’s sulking inside his tent.

Formulae: these repeated scenes - such as a warrior arming for battle, or someone performing a sacrifice - generally involve the same steps each time they occur in the poem, but can be shortened or lengthened to suit the poet’s purposes. The more a formulaic scene has been elaborated, the more important or pivotal we can expect what follows to be.

Extended Similes: these similes often compare a hero to something more familiar to the everyday lives of the intended audience. They ground the action, add vividness, and expand the poem beyond the restricted lives of heroes at war to include the more domestic worlds of women and children, as well as scenes of animals and nature.

It’s important to remember that the Iliad was originally performed. The poet sung or chanted the text, perhaps accompanied by a lyre, to an audience. The stylistic features that might seem repetitive to us as 21st century literature readers would have not only aided the poet in his composition, but also helped the original audience to find their place in and follow the story more easily.

Who was Homer?

In short, we don’t actually know. The Iliad was composed before written biography or written history had been invented, and we don’t have any definite facts about who Homer was, where he came from, when he composed the Iliad, how he composed it, or even if he actually existed at all.

It’s generally accepted that the Iliad was composed orally and first written down around 750 BC. By the 5th century BC we know that multiple versions (albeit with minor differences) were in circulation throughout the Greek-speaking world. The earliest manuscript we have is from the 10th century AD, and is based on a version compiled in Alexandria around the 2nd/3rd century BC.

There is speculation about whether Homer composed the poem orally and then wrote it down, whether he hired someone else to write it down, whether it was written down many years later, or whether the poem was composed by multiple people, over multiple generations.

Robin Lane Fox (in his Homer and his Iliad) has an argument that I’ve found particularly compelling: that Homer dictated his poem to a scribe, who was perhaps one of his children, to give as a kind of inheritance after his death. The children of Homer may have performed the poem, sold copies of it to other performers, and from there spread it around the Greek-speaking world.

Where and when is the Iliad set?

The Iliad is set towards the end of the 10 year Trojan War. Most of the action takes place on the plains, between the Greeks’ beached ships and the walled city of Troy.

The Iliad is set in a remote ‘heroic’ age, where people were better, stronger, and closer to the gods than people were in Homer’s own time. The setting has been described as Mycenaean and although there are elements of Mycenaean culture in the poem, Homer blends this with contemporary/near-contemporary culture and his own imagination. It’s important to remember that the Iliad is a work of fiction, not history.

The original audience would have been familiar with stories about Troy and I like to think about their response to the Iliad in the way that we might respond to a work of fanfiction or an adaptation of a piece of media that we already know: our enjoyment doesn’t come from wondering what will happen, because we already know that - it comes from finding out how and when it will happen.

We begin in media res: Homer assumes that we know who the characters are, and why they are in Troy. Agamemnon has led the Greek forces - comprising many heroes/leaders and their troops from many places - against Troy after Paris, a prince of Troy, ‘abducted’ Helen, the wife of Agamemnon’s brother, Menelaus.

What is the Iliad about?

Life, death, grief: what it means to be human.

The heroes of the Iliad are not like ordinary humans, the poet tells us: they are closer to the gods, stronger and more beautiful. They are excessive in both their actions and their emotions, and can seem to behave almost childishly in terms of their entitlement.

Achilles’ rage is one of these excesses. His decision to withdraw from the fighting after Agamemnon publicly dishonours him results in countless deaths on the Greek side - and this rage, when transferred from Agamemnon to the Trojans following Patroclus’s death, results in countless deaths on the Trojan side, too.

War was a fact of life for the Iliad’s original audience, and the poet presents it as multifaceted. War can be both glorious and devastating. It is a means by which the heroes can achieve great glory, but it also brings immense suffering - especially to the women and children left behind once the battles have been won and lost.

Kudos is the Ancient Greek word for what we roughly translate as glory. Heroes often gain kudos by performing well in battle.

Kleos is the fame that ensures the hero’s name (and kudos) lives on past his death through speech, memory, monuments, and song - like the Iliad itself.

Timē is a particular kind of honour or ‘worth’ that shows how a hero is regarded by his community - its opposite, Aidōs, shame, is to be avoided at all costs. Heroes’ aidōs is appealed to when they’re being encouraged to fight. Achilles’ timē is threatened when Agamemnon takes Briseis from him.

Heroes are motivated by gaining kudos, kleos, and timē, physically manifested in the form of ‘prizes’ - food, armour, treasures, or even enslaved people - decided on and shared out by their fellow warriors after battle has been won.

The gods are deeply involved in the heroes’ lives. There’s something Hunger Games-esque about the way they watch the battle unfold from their comfortable existence on Olympus, but they descend to the mortal realm, too. Sometimes they act discreetly - like when Athena discourages Achilles from killing Agamemnon during their argument - but sometimes they are more direct. Apollo sends the plague that leads to Achilles and Agamemnon’s argument; various gods protect their favourites by deflecting their opponents’ weapons or removing them from the battlefield entirely.

Some gods (Hera, Athena) support the Greeks and others (Aphrodite, Apollo) support the Trojans. Zeus is largely impartial, though the poet tells us at the very beginning that we will see his plan, his will, unfold throughout the course of the Iliad, and beyond.

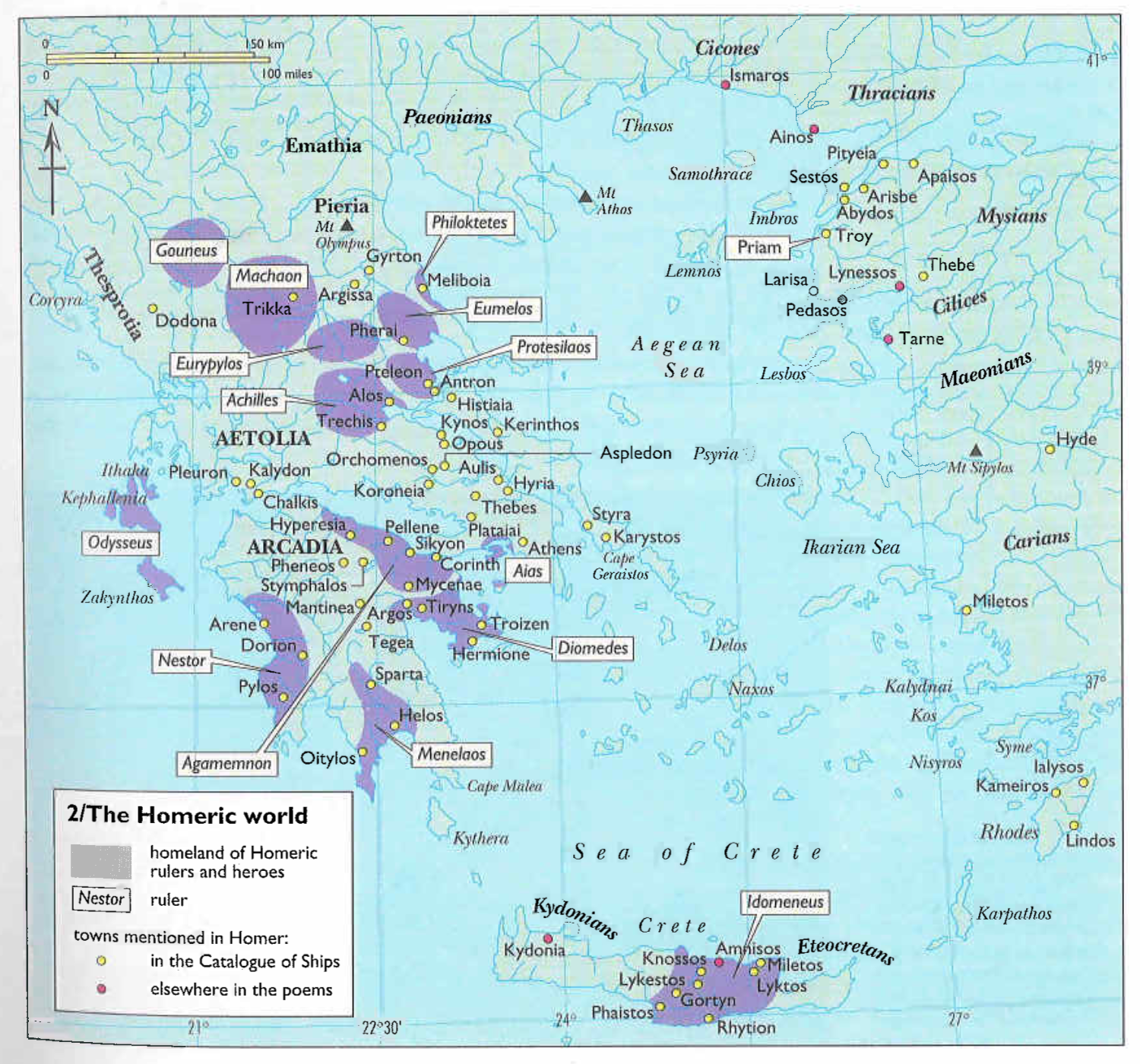

Map of the Homeric world

There’s nothing I love more than a book that includes a good map. My translation of the Iliad has five excellent ones, but even then it can be quite tiresome to keep flipping backwards and forwards as I’m trying to read. So I’ve included this map, hoping it will help you to navigate some of the unfamiliar names and places in the Iliad - particularly in the long Catalogues that you’ll find in Book 2!

Character guides

Achilles (Greek) ‘swift-footed’

The son of Peleus, king of Phthtia, and the sea-nymph Thetis, Achilles is the greatest warrior of the combined Greek army at Troy and leads the Myrmidons from Phthia. He is proud to the point of entitlement, quicktempered, and stubborn. When Agamemnon takes his war prize, Briseis, Achilles is furious and withdraws from the fighting, causing much suffering and loss of life on the Greek side.

Agamemnon (Greek) ‘lord of men’

King of Mycenae and brother to Menelaus. As the wealthiest of the Greeks’ kings and the leader who brought the largest number of troops, Agamemnon is the overall leader of the army. He is arrogant, tactless, and self-serving. He throws the Greeks into crisis when he dishonours Achilles by taking his war prize in compensation for having to return his own

Hector (Trojan) ‘glorious’

The eldest son of Priam, king of Troy, and heir to the throne. He shows tenderness with his beloved wife Andromache and son Astyanax, but is vocally critical of his brother Paris’s cowardice. The greatest warrior of the Trojan army, Hector deeply feels the responsibility to protect his city and its inhabitants, even at great personal cost.

Helen (Greek/Trojan) ‘glorious’

The daughter of Zeus and Leda, queen of Sparta. A favourite of Aphrodite and labelled by the goddess as the most beautiful woman in the world. Helen was married to Menelaus and her abduction by Paris instigated the Trojan War. She expresses shame for the consequences of her abduction and shows contempt towards Paris for his cowardice.

Hera (Greek) ‘ox-eyed’

The goddess of marriage and women; wife (and sister) of Zeus. Hera is stubborn and wilful and often disobeys Zeus, going behind his back to secretly plot with Athena to destroy the Trojans - continuing even when Zeus threatens her with punishment. Her hatred of Troy stems from the Judgement of Paris, where Paris named Aphrodite the most beautiful goddess over her and Athena.

Menelaus (Greek) ‘warlike’

The king of Sparta and younger brother of Agamemnon. The abduction of his wife, Helen, was the catalyst for the war, but Menelaus seems less arrogant than his brother and more concerned with fighting than leading the troops. He is courageous in battle, eagerly agrees to the duel with Paris as a means to quickly end the war, and fights him ferociously.

Odysseus (Greek) ‘master of strategies’

The king of Ithaca. Although Odysseus brought just a small contingent of troops to Troy, he is well-respected for his cunning and intelligence. He is a good fighter, killing many Trojans when he enters battles, but his most prominent skill is his cleverness. He uses persuasion and oratory to both rally the troops and mediate between Agamemnon and Achilles.

Paris (Trojan) ‘godlike’

Son of Priam and brother of Hector. A favourite of Aphrodite, Paris seems more at ease in his bedroom surrounded by comforts and the beautiful Helen than on the battlefield. He is self-centred and vain, often criticised by Helen and Hector for his cowardice, and has to be persuaded to fight. His abduction of Helen instigated the war.

Patroclus (Greek) ‘brave’

Beloved friend and companion to Achilles, they grew up together and often seen together in the Iliad. Patroclus is often described as kind, and is more compassionate than Achilles. He cares deeply for the plight of the other Greeks, though his compassion doesn’t hold him back on the battlefield and he fights ferociously against the Trojans. His death is the only reason Achilles returns to the fighting.

Priam (Trojan) ‘old’

Elderly king of Troy who presides over the city and its inhabitants while his fifty sons battle to defend them. Priam is kind and compassionate, especially towards Helen, whom he doesn’t blame for the war. He is not as arrogant and proud as the younger heroes, though he shows great bravery in approaching the Greek camp to supplicate Achilles for the body of his son, Hector.

Thetis (Greek) ‘silver-footed’

A sea nymph and mother of Achilles. Thetis cares deeply for her mortal child and shares in his outrage after he is dishonoured by Agamemnon. She is determined to help Achilles and eloquently persuades Zeus to punish the Greeks on her son’s behalf. Although she knows she cannot save Achilles’ life, she does everything she can to help him to achieve glory.

Zeus (impartial) ‘cloud-gatherer’

Husband (and brother) of Hera; god of the sky, thunder, and justice. Zeus claims impartiality in the war and often tries to prevent the other gods from exerting influence over the outcome, but he agrees to help Thetis to help the Trojans for Achilles’ sake. Zeus has frequently been unfaithful to Hera and is quick to anger and threaten her with physical violence when she plots against him.

Book-by-book summaries

Book One: the plague and the argument

The proem introduces the scope of the poem: Achilles’ rage. We learn that the Greeks have attacked a nearby town and taken, amongst other ‘prizes’, two women: Chryseis was given to Agamemnon, Briseis to Achilles. Chryseis’s father comes to ransom her. When Agamemnon rejects him, he prays to Apollo. Apollo sends a devastating plague to the Greek camp.

Ten days later, Achilles summons an assembly. The prophet Calchas says that Apollo will only be appeased when Chryseis is returned to her father. Agamemnon demands another ‘prize’ in compensation for losing Chryseis: Achilles’ prize, Briseis. Furious and humiliated, Achilles threatens to go back home with his troops. The argument intensifies, until the goddess Athena has to intervene to prevent Achilles from killing Agamemnon.

‘The Greeks will all be longing for Achilles

one day and you will have no power to help,

and you will grieve and many men will die

at Hector’s murderous hands. Then you will tear

your heart inside you in a bitter rage

because you failed to pay the best Greek fighter

proper respect.’

Agamemnon orders Odysseus to escort Chryseis back to her father and sends his heralds to Achilles’ tent to take Briseis. Achilles vents to his mother, the sea-nymph Thetis, and asks her to ask Zeus to give victory to the Trojans.

Chryseis’s father, now she is safely returned, prays to Apollo to stop the plague. Odysseus feasts with them.

Thetis travels to Olympus and supplicates Zeus. Zeus is reluctant to help because his wife, Hera, hates the Trojans, but is eventually persuaded. Hera is furious, and Zeus threatens physical violence when she rebukes him. Hephaestus advises her to submit to Zeus’s will and entertains the gods, lightening the tense atmosphere.

Book Two: the dream and the catalogues

Zeus sends a false dream to Agamemnon, telling him he will be able to take Troy if the Greeks attack immediately. Agamemnon wakes and decides to ‘test’ the army by pretending they are going to surrender and return to Greece. Delighted, the Greeks hurry to prepare their ships.

With a yell

they dashed towards the ships. Beneath their feet

dust rose. They told each other, ‘Seize and drag

the ships towards the bright sea! Dig the furrows!’

Their shouting reached the sky. They longed for home.

Hera sees what the army are doing and warns Athena, who tells Odysseus to stop them. He uses taunts, threats, and encouragement to regroup the troops.

Assembly reassembled, a lower ranking soldier, Thersites, rebukes Agamemnon. Odysseus beats him into submission. Agamemnon orders the troops to arm themselves for battle and makes a sacrifice to Zeus.

The poet lists the Greek cities that have sent troops to Troy and who their leaders are.

Zeus sends the messenger goddess Iris to Troy to warn them of the Greek advance. The Trojan troops are drawn up on the plain between the city and the Greek camp, led by Hector, prince of Troy.

The poet lists the Trojan leaders and their allies.

Book Three: another catalogue and the duel

The Greek and Trojan armies advance towards each other.

Paris challenges the Greeks to a duel, but retreats when Menelaus accepts. Hector scolds Paris for his cowardice and Paris agrees to duel Menelaus: the winner will take Helen, along with other prizes, and end the war. Menelaus demands an oath be sworn.

Iris, in disguise, visits Helen, who is weaving inside the palace, to tell her about the duel. Helen goes to the city walls to watch the battle and finds the Trojan elders already gathered there. King Priam is kind to her and asks her to identify the Greek heroes for him: she points out Agamemnon, Odysseus, Ajax, and Idomeneus. She wonders where her brothers, Castor and Pollux, are.

Priam is summoned to swear the oath with Agamemnon. Priam returns to Troy, while Hector and Odysseus mark out the boundaries of the duel and Paris and Menelaus arm themselves.

Menelaus and Paris both throw their spears. Menelaus hits Paris’s helmet with his sword, and breaks it. Menelaus grabs Paris and drags him along the ground; he retrieves his spear, but before he can attack again, Aphrodite rescues Paris and takes him to his bedroom inside the palace.

Aphrodite orders Helen to go to Paris. She does so, reluctantly, and criticises Paris for his cowardice before going to bed with him.

‘Stubborn girl! You must not make me angry,

or in my rage I will abandon you,

and start to loathe you with as deep a passion

as I have loved you as my friend till now.

I shall devise a strategy to make you

loathed and abhorred by both the Greeks and Trojans,

and you shall die a dreadful death.’

On the plain, both armies search for Paris. Agamemnon demands Helen since Menelaus won the duel.

Book Four: the broken oath

On Olympus, Zeus suggests that the war should end since Menelaus won the duel. Furious, Hera demands Troy’s complete destruction. Zeus relents and sends Athena to make the Trojans break the oath.

She persuades the archer, Pandarus, to shoot Menelaus. Menelaus is wounded; concerned for his brother’s life, Agamemnon summons the Greeks’ doctor, Machaon, who tends to the wound.

‘But Menelaus,

my grief for you will be unbearable

if you should die and fill your span of life.’

Agamemnon rallies the Greek leaders with a mixture of praise and rebuke. He criticises Diomedes for not living up to his father’s deeds.

Battle ensues. Greater Ajax and Odysseus kill many minor Trojans. Some of the gods descend: Athena supports the Greeks, and Apollo the Trojans.

Book Five: Diomedes’ aristeia

Athena gives Diomedes strength and leads Ares away from the battlefield. Pandarus wounds Diomedes; Athena gives him extra strength and the ability to see the gods on the battlefield, but warns him to avoid fighting any of them except for Aphrodite.

Diomedes is ruthless in battle, killing every Trojan he encounters. He kills Pandarus and wounds Aeneas; when his mother, Aphrodite, comes to help him, Diomedes wounds her as well.

Aphrodite flees to Olympus. Her mother comforts her and Zeus warns her to stay away from the battlefield.

‘The violent fighting

is now no longer Trojans against Greeks.

The Greeks are fighting the immortal gods!’

Apollo looks after Aeneas in Aphrodite’s stead. Diomedes attacks him four times; Apollo warns him to stop, takes Aeneas off the battlefield, and urges Ares to fight with the Trojans.

Ares fights alongside Hector, terrifying the Greeks - even Diomedes. Ajax and Odysseus kill many Trojans; Hector kills many Greeks.

Hera rallies the Greeks and Athena encourages Diomedes to attack Ares. She drives his chariot and helps him to wound Ares, who flees to Olympus and complains to Zeus. Zeus is unsympathetic. Hera and Athena return to Olympus.

Book Six: Hector and Andromache

The battle continues. Menelaus considers sparing the life of a Trojan he has overcome, until Agamemnon rebukes him.

The Trojan prophet Helenus advises Hector to return to the city to ask the Trojan women to pray to Athena.

Diomedes meets the Lycian Glaucus, a Trojan ally, on the battlefield and they discover that their ancestors were guest-friends. They agree not to fight each other and exchange armour as a token of their friendship.

‘So let us now avoid each other’s spears,

even amid the thickest battle scrum.

Plenty of Trojans and their famous allies

are left for me to slaughter, when a god

or my quick feet enable me to catch them.’

Hector reaches Troy. Hecuba offers him wine; he refuses, and asks her to pray to Athena. Hecuba gathers the other Trojan women and takes an offering to Athena, who does not listen.

Hector finds Paris and criticises him for not joining the fighting. While Paris goes to get ready, Helen disparages him and asks Hector to stay with her. Hector refuses.

Hector meets his wife, Andromache, near the city walls. She begs him to fight away from the battlefield, where there is less danger, but he refuses, citing his duty to the city and its people. He kisses their baby, Astyanax, who is frightened by the crest on his father’s helmet. Hector departs.

Andromache and her slaves mourn Hector as though he has already died.

His loving wife set off for home, but kept

twisting and turning back to look at him.

More and more tears kept flooding down her face.

Hector meets Paris at the city gates and they advance for battle together.

Recommended resources

Podcasts

Natalie Haynes: The Iliad

The entirety of the Iliad recounted in just half an hour.

In Our Time: The Iliad

Edith Hall, Barbara Graziosi, and Paul Cartledge discuss the Iliad with Melvin Bragg.

The Forum: The Iliad

Bettany Hughes discusses the Iliad with Stathis Livathinos, Antony Makrinos, Folake Onayemi, and Edith Hall.

Let’s Talk About Myths, Baby!: The Iliad

Summaries, explanations, and discussions of each book of the Iliad.

Art

The Iliad

I’ve curated a selection of paintings and sculptures from British galleries that feature scenes from the Iliad.

Wikimedia: The Iliad in art

More artworks featuring scenes from the Iliad.

Wikimedia: Trojan War in ancient Greek pottery

A selection of ancient Greek vases featuring scenes from the Trojan War.

Flaroh

Illustrations of many figures/scenes from Greek and Roman history, including those featuring in the Trojan War.

Merch

Flaroh

Illustrations from Greek and Roman history/mythology, available on a variety of products.

Greek Myth Comix

Printable posters, colouring books, playsets(!) and more, featuring scenes from Greek mythology.

Scents of Elysium

Candles inspired by mythology, using scents available to the ancient Greeks.

Plato’s Fire

My jewellery! Inspired by old books and ancient epic literature.

Videos

MoanInc: Iliad playlist

Book-by-book summaries and detailed explanations of the events of the Iliad.

London Review of Books: The Iliad

Emily Wilson, translator of the Iliad, discusses her work with Edith Hall. Juliet Stevenson and Tobias Menzies read extracts of Wilson’s translation.

Classics for All: Homer, Iliad

Sections of the Iliad, read aloud in the original Greek.

Greek Myth Comix: Explaining Ancient Literature

Helpful explanations of features of Homeric epic, including similes, epithets, and formulae.

Hay Festival: Why Homer Matters

Adam Nicholson and Paul Cartledge discuss how Homer can still be relevant to us today.

Gresham College: The Iliad vs Troy

Edith Hall discusses the differences between Homer’s epic and the 2004 Hollywood blockbuster about the war.

Books

Historical Atlas of Ancient Greece, Robert Morkot

The maps are helpful for understanding the space and context of the Trojan War.

A Companion to the Iliad, Malcolm Willcock

A commentary on the Lattimore translation, but useful for others too.

Homer and his Iliad, Robin Lane Fox

A more detailed introduction to Homer, epic, and the themes of the Iliad. Especially detailed on the poem’s (potential) origins and author.

The Ancient Greece of Odysseus and The Greek Armies, Peter Connolly

The illustrations, maps, artefacts, and reconstructions are really helpful for visualising the Iliad and its characters.

Homer: The Iliad, William Allan and Homer: The Iliad, Michael Silk and Homer, Barbara Graziosi and Homer, Jasper Griffin

All good introductions to Homer, epic, and the themes of the Iliad.

What to read next

Modern

PROSE:

The Song of Achilles, Madeline Miller

Achilles and Patroclus’s love story.

The Silence of the Girls, Pat Barker

The Iliad from Briseis’s point of view.

The Women of Troy, Pat Barker

The Iliad from its women’s points of view.

A Thousand Ships, Natalie Haynes

The Iliad from its women’s points of view.

GRAPHIC NOVEL:

The Trojan Women, Euripides/Anne Carson/Rosanna Bruno

An adaptation of Euripides’ play in graphic novel form.

DRAMA:

Andromaque, Jean Racine

An adaptation of Euripides’ play.

Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, Anne Carson

A loose adaptation of Euripides’ Helen, set in 1963 New York.

Ancient

TROY STORIES:

Ajax, Sophocles

The battle for Achilles’ armour.

Philoctetes, Sophocles

The return of Philoctetes.

Rhesus, Euripides

Book 10 of the Iliad.

THE WOMEN OF TROY:

The Trojan Women, Euripides

What happens after Troy is defeated.

Andromache, Euripides

Andromache enslaved.

Hecuba, Euripides

Hecuba enslaved.

HOMECOMINGS FROM TROY:

The Odyssey, Homer

Odysseus’s return.

Agamemnon, Aeschylus

Agamemnon’s return.

BEYOND TROY:

The Aeneid, Virgil

Aeneas’s escape from Troy.

ALTERNATE TROYS:

Helen, Euripides

Helen was never in Troy.